The Irish Wake

A Talk by Rev. Alan Stewart on 24 September 2025

How the Irish teach us to live, love and die

(The talk is available in pdf and audio format at the bottom of the page: go straight there)

A sabbatical is an incredible luxury, and I’m hugely grateful for everything these three transformational months have given me. One aspect of a sabbatical is study, and I chose to research and explore the ancient rituals surrounding the Irish Wake.

Why? Well, a year or so ago, I read a wonderful book called ‘My Father’s Wake’, subtitled ‘How the Irish teach us to live, love and die’, (a great title which I’ve obviously nicked for this talk!) It’s written by the Irish journalist and bardic poet Kevin Toolis, and it’s the story of his own experience of the healing power of the Irish wake. It was this extraordinary memoir and my own experience of the wake which inspired me to delve deeper, to explore how this ancient rite might speak to an Irish priest ministering here in England, in a very different culture, where death, I think, is probably more feared and definitely less seldom spoken of.

Also, I have to confess that as I age, I’ve noticed just how much more my own mortality, my death, is casting a shadow across my present. It is indeed a sobering thing to accept the obvious, that none of us are immortal, even though we often live as though we are. So, I have also been reflecting on how I might better befriend my own mortality.

My first and only experience with the Irish wake was when my mother died in 2012. I remember receiving the news that she was nearing the end of her life, and as I made the journey home from England to be with her, alongside all the heartbreak and mess of grief, there was also a discomfort, a dis-ease as I contemplated the wake that would follow. The idea of such a public sharing of grief clashed with my own strong desire to hold my grief in a much more private space.

Little did I realise that the wake was exactly what I needed.

So, during this sabbatical, I’ve read books and watched YouTube interviews and talks. I’ve road-tripped across Ireland, visiting an actual Museum of the Wake, and chatted with strangers along the way, most memorably with Geraldine, a wild swimmer on this West coast beach who shared with me her experience as well as her bottle of holy water!

Before I share with you these holy things I’ve learnt, it’s important to say that traditions vary between urban and rural, between Catholic and Protestant, and they are changing. Many of the old traditions are disappearing and some only remain within the more isolated island communities.

The wake begins at the moment of death. Kevin Toolis describes how, instinctively, in the moments before his father’s death, his sisters began to recite, ‘Hail Mary, Mother of God… pray for us sinners now and at the hour of our death’, softy, and then louder as one by one others joined in this cradling of prayer. These familiar and precious words would be the last sounds his father heard, his final lullaby to see him safely into death.

In Toolis’s words, this was ‘an act of grace that forever bound the dying man and the watchers together in that moment’.

In bygone days, most people of course died at home, and ancient wisdom/superstition required that a window be opened to let the soul leave. This window would then be closed two hours later to prevent the soul’s return!

Mirrors were sometimes covered, either as a sign of respect – this is no time for vanity – or because some believed that another realm lay beyond, and the soul must not get trapped there.

Sometimes, bed clothes would actually be burnt, to cleanse the place of the spirit of Death.

Like W H Auden’s famous poem, clocks were stopped because from this moment everything has changed, and time has no meaning in grief. We now eat when we’re hungry, we sleep when we need to.

The body would be washed by the family or neighbours, and dressed in their Sunday-best, but left barefooted for this their last pilgrimage into the next life. A rosary would be placed within their hands and sometimes coins on their eyes to avoid them opening unexpectedly and scaring the ‘bejeezus’ out of everyone! The body would be laid out on a kitchen table, or if the table wasn’t big enough, a door would be taken off its hinges and used. These days, the deceased will usually be laid out more privately in a bedroom. Candles were sometimes placed at the head and the feet of the deceased, so the body would never be left in darkness.

And then, for up to three days, people take turns staying awake with the body through the night, guarding and keeping them company.

No tear was shed until the laying out was complete and it was certain that the soul had indeed left.

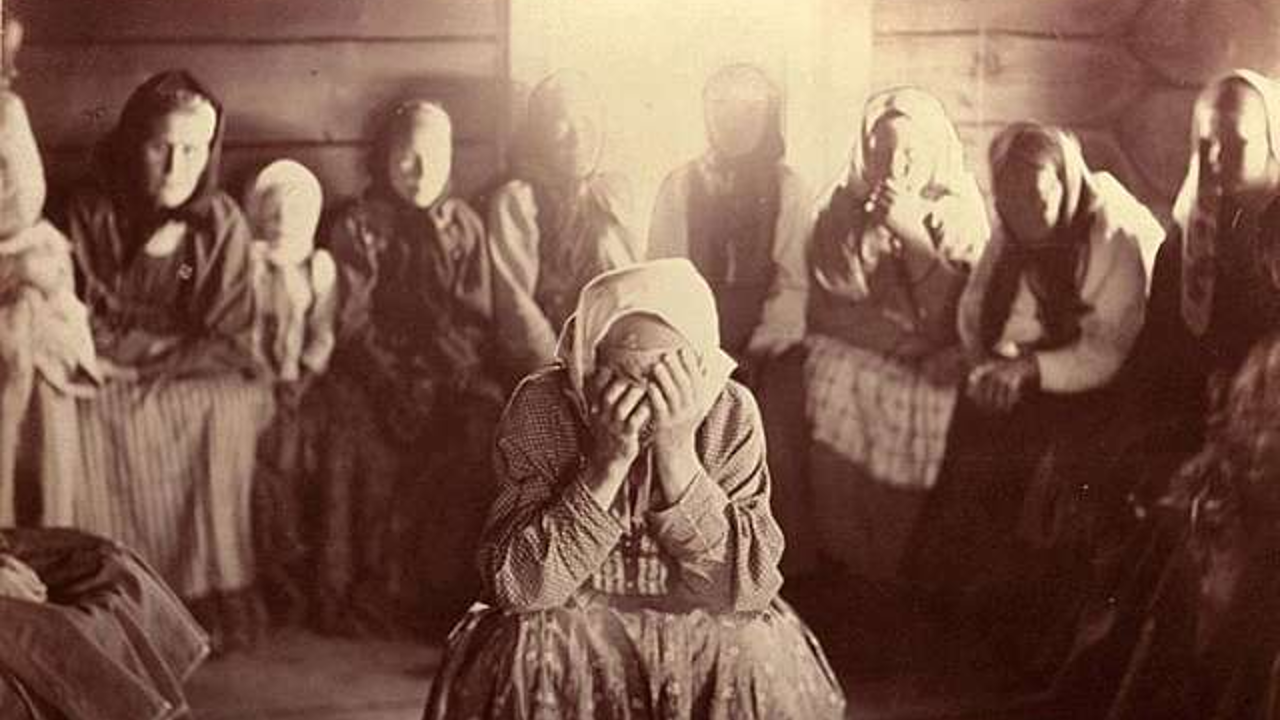

And then, in days gone by, the keening might begin.

Keening is an ancient rite that has all but disappeared. It’s the oldest music of womenkind, dating back as far as the wailing daughters of Jerusalem and further. Traditionally it’s done by [A group of people sitting in a room AI-generated content may be incorrect.] women, ‘minstrels of the dirge’, ‘midwives of death’, who would wail and sing ancient laments. Sometimes, professional keeners were paid to sing and cry. The oldest account in Ireland comes from 1689, which speaks of hired keeners who, before they could begin, had first to knock back several glasses of whiskey! Sometimes, extemporary poetry would be recited detailing aspects of the life of the deceased. One report from Kildare in 1683 talks of ‘shrill cries and hideous hootings’ which could be heard for miles!

These paid keeners, or some might say ‘artificial’ mourners, were heavily discouraged by the clergy, as were other aspects of the wake, but more of that later.

The Irish are not afraid to weep publicly. During the three days, as new people arrive, a fresh wave of public lament might begin.

When we were driving through County Mayo, we were listening to the local radio station. And three times a day, a bell would toll and then the names of all the deceased in the county would be read out. The word ‘wake’ was actually never used. Always, they would talk about the body ‘reposing’, and would offer either an open invitation for people to come to the house at any time, or give a time slot where people were welcome to come. Occasionally, they would speak of the house being ‘private’; family only.

In the main, however, for the Irish, death is a communal thing.

The whole neighbourhood mobilizes, makes sandwiches and cakes, and everyone - family, friend, neighbour - is expected to come to the house of the bereaved, to eat and drink endless tea or something stronger, to tell their stories, to share their grief; to laugh, to cry, sometimes to sing and make music. And time after time, person after person will shake the hand of the bereaved and say the same thing - ‘Sorry for your troubles,’ ‘Sorry for your troubles,’ ‘Sorry for your troubles’.

As an introvert, I was dreading this. And yet, in reality, I found the company of family and stranger incredibly comforting. I learnt things about my mum I didn’t know. I laughed a lot. I felt held in the embrace of a community, most of whom I didn’t know from Adam or Eve. I learnt that grief is a ‘we’ thing as well as a ‘me’ thing.

My mum was laid out in a bedroom, in an open wicker coffin, trailed with wildflowers. Each person, including children, was expected to come and pay their respects, to speak what we needed to, to weep over or to argue with the dead, to say a prayer if we felt inclined. Nothing was left unresolved. We are encouraged to touch the body, to stroke their hair, to kiss them. As I sat with the body of my mum, there was a stillness and a normality about it. It felt like the most natural, most human, most real thing in the world. It felt deeply healing and, yes, sobering, too. As sure as anything, we all die.

Seeing, touching, is believing.

Kevin Toolis recounts his first wake, aged five, when his mum lifted him up to view the dead body and said, ‘Touch him, it will make you less afraid’. The wake has a way, I think, of helping ease the fear of death. Kevin Toolis, in another book, intriguingly entitled ‘Nine Ways to Conquer Death’, speaks of what he calls a ‘Western death cowardice’, which results, he says, in death loneliness. Our fear of speaking death’s name or having conversations about it has created a vacuum, a loneliness in us.

The Irish talk openly about death and have some great turns of phrase for the dead, occasionally employing a little gloss or a white lie where needed; ‘Sure, she looks like herself’, ‘God, your mother always had lovely hair’, ‘Sure, isn’t it happy for him’, ‘Sure, all the pain of the cancer has gone from his face’.

Death is part of the conversation of everyday life.

The wake is a grieving, but it is also a celebration of life and life’s renewal, so children, for example, are especially welcome because, of course, they are the future.

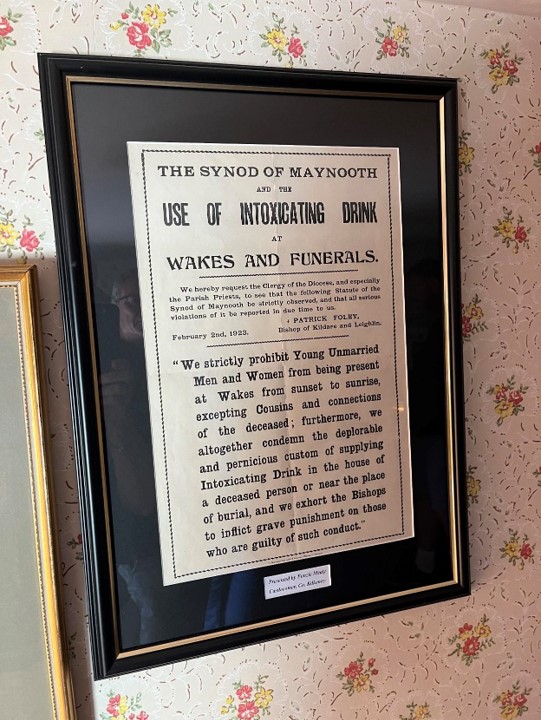

There’s lots of laughter at wakes and, yes, sometimes alcohol! In the Museum of the Wake in Waterford, there’s a public notice from the Synod of Maynooth in 1875, forbidding young unmarried men and women from attending wakes and condemning the ‘deplorable and pernicious custom of supplying Intoxicating Drink (capital I, capital D) at wakes, requesting the local Bishop to inflict grave punishment on those who are guilty of such conduct! Exact details of that punishment are not recorded!

In days gone by, there were traditions of rowdy games being played at wakes. In his book ‘Irish Wake Amusements’, Seán Ó Súilleabháin lists storytelling, dancing, card-playing, tongue twisters, agility and endurance contests, mischief making, catch games, hide and seek, fights, versions of spin the bottle, and even mock marriages! All of this would be overseen and orchestrated by a male jester called a Borekeen. Often, young men and young women would attend a wake with the sole intention of securing a kiss, hence the prohibition of the synod of Maynooth! These ‘wake amusements’ have all but disappeared.

In bygone days, clay pipes or cigarettes would be gifted to the mourners, and the home would fill with smoke, another way, perhaps, of keeping Death at bay. Snuff would sometimes be placed on the body itself so that those paying their respect could take a pinch. It was also a clever way of ensuring that no one took advantage of the hospitality of the house; you only pay your respects once!

Wakes, contrary to some opinion, are not piss-ups. They are part of the Irish tradition of ‘Rambling Houses’, where people dropped into homes to listen to music and share news.

You’ll know that over the centuries, the Irish emigrated in huge numbers all over the world. In Dublin, I was fortunate to visit the Museum of Emigration. Because families knew that they would almost certainly never see those loved ones again, they would sometimes hold a Living Wake, a farewell party.

The artist Grayson Perry, in his extraordinary Channel Four series Rites of Passage, helped a terminally ill man called Roch (Roke) to create his own Living Wake, a gathering of all those who loved and were loved by him, where he was the guest of honour. Perry made a ceramic funeral urn decorated with pictures from Roch’s life, and each person present had the opportunity to come forward, tell their stories, say their final [A person with an oxygen mask on his face AI-generated content may be incorrect.] goodbyes and then place inside the urn something that reminded them of their husband, father and friend. Roch himself spoke at his own wake and his words were a gift to each one there, as were their words and presence to him. It’s one of the most beautiful and moving things I’ve ever had the privilege to watch, and I think it’s one of the greatest ideas ever; why should we wait to say these things?

The wake is a catharsis for the most powerful emotions we will ever experience. Kevin Toolis again says, ‘A wake is an encompassing, an act of moral solidarity within a community to overcome the rupture of an individual death and a prescribed ritual where the physicality of death, a corpse, is tamed, neutralised, and assigned a place in the order of the world. Feasting, and drink, to replenish the hungers of the mourners and entice the bereaved away from the abstinences of grief, is an intrinsic element’. He calls this a communal act of care.

For the Irish, death is a communal activity. In Irish, there is something called the Meitheal (pronounced mehil). It’s an ethos of community-based cooperation and mutual support. Often, it can take the form of a work party, for instance to bring in the hay or build a barn. It’s a coming together, and the wake and the subsequent funeral embodies the Meitheal. The community makes sandwiches, feeds and supports the grieving. For family and friends, it is an honour to carry the coffin. In some communities, there are no professional pallbearers or grave diggers, the community steps in. It’s seen as a moral obligation to visit the dying and the dead, to attend the wake and the funeral; to shake the hand of the grieving. Hundreds, often, will line up to do this, so much so that funeral directors often advise family to remove rings to avoid bruising. Time after time after time, those same words, over and over: ‘Sorry for your troubles’, as if each handshake is saying, ‘life has changed, they’re dead’.

In contrast to our Western silencing of death, the Irish are under a social obligation to publicly acknowledge the loss of the deceased to the bereaved the first time they meet after the death.

This is not Ireland, so what small things might we want to do differently?

Toolis says this: ‘We can all use the small powers we do have, the phone in your pocket, to reconnect and recreate these ancient bonds. Instead of shunning, we can reach out to the Other around us and offer ourselves to play a part in the visiting of the sick, bearing witness with the dying, even the carrying of the coffin. Speak out, offer our sorrow and condolences, and connect’. ‘To be truly human’, he writes, ‘is to carry the burden of your own mortality and strive in grace, to help others carry theirs, sometimes lightly and sometimes courageously’.

If we are the one doing the dying, don’t be afraid to share your death. Reach out and invite friends and family to see you, to say goodbye. Think about holding a Living Wake. Find yourself a bean chabrach (Baan Kah bruh), a midwife of death, someone to be with you in your dying, and take responsibility when you are no longer able. Order your affairs, wills, unresolved conflicts; forgive yourself; say everything you never got round to saying.

The dead belong to those who love them, so go see the dead, touch them, speak with them, pray for them.

Hug the bereaved. Bring them shopping, help shift furniture. Go to more funerals and take your children with you. Speak to your children about death. There are some lovely books. Go out of your way to shake the hand of the bereaved the next time you see them. Offer what help you can. Speak of the dead who shaped your life more often, so that they live on. Visit their graves.

Death, I’m afraid, is compulsory. And, actually, that’s good. To live forever would not only be a huge drain upon this earth, it would be unbearable. The world makes sense to us because we die, not because we don’t. Death gives life its meaning. It reminds us that life is fragile and therefore precious, so take joy in the living.

Lean into your mortality, recognise that death is actually nothing special, so integrate it a little more into life.

We hear people speak of a ‘good death’. Hopefully, that means a pain-free one surrounded by those we love. We should never live, love or die alone.

But how do we prepare for our own good death?

How do we live so that death doesn’t catch us unawares?

What do we do so that we don’t leave this world with too much unfinished business?

The Roman Catholic priest Ron Rolheiser speaks of the three seasons of our lives. The first is the ‘struggle to get our lives together’, to find our identity, to answer that question, ‘Who am I?’. The second, he calls the ‘struggle to give our lives away’, when we have responsibilities like mortgages or children or a partner; a learning to be less selfish. And the third, he calls ‘Learning to give our deaths away’; how do I live these last years, so that when I die, my death will bless my loved ones just as my life once did?’

He goes on to say, ‘What prepares us for death, anoints us for it’. In other words, we get ready for death by beginning to live our lives more fully. And how do we do that? We stretch our hearts, push ourselves to love less narrowly.

He tells the story of a young student he knew who was dying from cancer, who said, ‘There are only two tragedies in life and one of them is not dying young. These are the two tragedies: if you go through life and don’t love and if you go through life and don’t tell those whom you love that you love them’.

We prepare for death by loving deeply and expressing it. At Jesus’ anointing, he says that Mary has anointed him for death. In Rolheiser’s words, it’s as if Jesus is saying, ‘When I come to die, it’s going to be easier because, at this moment, I am truly tasting life. It’s easier to die when one has been, even for a moment, fully alive’.

So, we prepare for death by living more fully now. We prepare for death by working at loving more deeply, less discriminately, more affectionately and more gratefully. We prepare for death by telling those close to us that we love them. In this way, we befriend our death and it will never catch us like a thief in the night.

A last word about the dead. The musician Nick Cave, in his blog Red Hand Files, when asked how he prepares for a show and reflecting on the death of a friend, Dud, who he’d lost touch with and who recently had died, says:

To answer your question, I arrive at the venue about thirty minutes before the show begins. I usually have a room of my own where I change into my stage clothes, put on a little make-up, and do some vocal exercises. Then I sit in silence, with my eyes closed, for about fifteen minutes.

During this time, I bring to mind those dear to me who have passed away, focusing on each person individually, and silently solicit their presence. For someone of my age, this is a fairly substantial task. I assign specific qualities or powers to them that reflect their personalities, and I call upon those qualities.

I call on Arthur, for example, for his joyfulness; Jethro for his anarchic spirit; my mother for her courage; and my father for his dynamism. I also look to my old friend Mick Geyer for his diligence; Tracy Pew, Shane, and Conway for their subversiveness, disorder and wicked humour. I call upon Anita for her pure creativity and Roland for his extraordinary inventiveness, and so forth. I appeal to these individuals, and many more, much like a devout person might petition the saints, for assistance. I remember all these people and I feel a deep spiritual empowerment, so that when I take to the stage, I am carried along by this unearthly fraternity and their special powers. For me, this is an immense strength - an energy that illuminates what is truly meaningful and what is not.

Communing with the dead is, in that respect, as clarifying an exercise as anything can be. We are quickly reminded of what matters and what does not. And what matters at that moment to me, as I step onto the stage, is to give my best and not waste the opportunity I have been given. We musicians are in the business of transcendence, after all.

So, Melody, that is how I prepare for a concert, and that’s what I will do before I go on stage with Colin Greenwood tomorrow night in Rochefort. Although, tomorrow night I will be welcoming another person to this otherworldly assembly, Dud Green. I will assign to Dud the quality of vigilance or attentiveness, perhaps as a reminder to remain alert to the passing of time and to make contact, now and then - an email, a text, a phone call, a letter - with those who have slipped from my mind, those loved but unremembered, the forgotten living, while they are still with us.

An Irish blessing

‘May the wonders of this mortal world shine upon you.

May you live long enough to grow wise no matter how old.

And on the day that death comes, may you die on a good day in grace, surrounded by those you love’.

Download or listen to the talk

This article is available as a PDF DOCUMENT

And you can listen to the talk here: